Having been dry, for months, on both style and content, as you may have gleaned, I haven’t been writing creatively. Aside from a week of National Novel Writing Month – which I stopped when I realised I was less interested in my characters than I was in my word-goal – I’ve done very little to spark myself to interest, largely because, being back at university, I am busy enough with literature as it is.

Having been dry, for months, on both style and content, as you may have gleaned, I haven’t been writing creatively. Aside from a week of National Novel Writing Month – which I stopped when I realised I was less interested in my characters than I was in my word-goal – I’ve done very little to spark myself to interest, largely because, being back at university, I am busy enough with literature as it is.

Last year I found that one of the many benefits of studying literature is that as I read and discuss and study, ideas for my own writing organically rise to the surface of my consciousness. Art spawns art. This is has proved to be less true in my second year, but every now and then I’ll come across something that I’d like to try.

When I was in the upper school I spent a month of each of my four years studying the history of literature. By looking at a variety of texts from Gilgamesh to Oedipus Rex to The Tempest to the Lyrical Ballads to Riddley Walker, I was able to gain a rather comprehensive overview of the evolution of literature, and one of the main things I remember from these classes is writing poetry. Whatever era or subject we were studying, we were encouraged to write poetry in a similar style. So I wrote sonnets and villanelles; I wrote in iambic pentameter and trochees; I wrote quatrains and free-verse; and I often enjoyed the freedom of subject juxtaposed with the structure of the form. I also very much liked the way in which I now, in a contemporary setting, I am free to pick and choose from past forms and find one that will fit whatever poem I would like to write.

However, since leaving school, I haven’t written much poetry. There are a few poems on this site, and even one I am quite fond of, but for the most part they’ve been written quickly and without all that much care1. Poetry is by no means a dying art – there are plenty of poets out there if you care to look for them! – but it is less in the public eye, and has been somewhat usurped by the rise of the novel.

It’s ironic really: when the novel first appeared (around the beginning of the 18th Century), it was looked down upon as a lowbrow form of literature, not fit to sit on shelves besides poetry, romance and epics. Novels were printed to be read once and thrown away, like we might do with a newspaper. Yet now the BBC covers the Man Booker Prize every year, extensively, and I can’t even call to mind the name of a poetry prize – although, again, there are plenty of them.

But I digress…

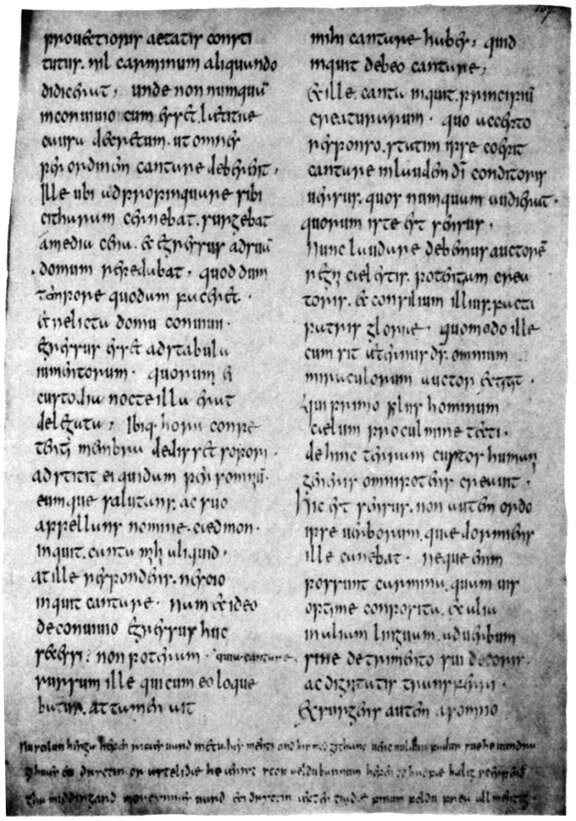

The reason, I suppose, that I haven’t written much poetry lately is that usually my creative ideas are narrative ideas. Of course, I could write narrative poetry, but it was never my preferred style. My ideas seemed to lend themselves far better to prose. However, given my lack of narrative inspiration, I thought perhaps now would be a good time to return to looking at poetry. This realisation is, of course, heavily influenced by what I’m currently studying – Troilus and Criseyde (Chaucer) – and a lecture I had the other night on Early English Poetics. The guest lecturer himself – whose name I wish I could give you, but for privacy reasons I can’t – writes modern poetry in the style of early English poetry. Whilst there are various different forms, I was particularly interested in the structure used in Caedmon’s Hymn, which I looked at a few weeks ago.

Given the structure of this poem and the difference in language, writing in this form using modern English is no small feat. In Old and Middle English (OE, ME), the stresses in words are not standardised, as they are now. For example: in the word ‘genius’ we naturally put the stress on the first syllable – ‘genius’ – and it would sound strange if we were to put it on the second – ‘genius’ – or the third – ‘genius.’ However, in OE and ME, the stresses are flexible, and can change depending on the context and how they are spoken. Therefore OE and ME lend themselves very well to poetry, and when early English poetry was being written, the language was often changed and manipulated to serve the form itself.

The structure used in Caedmon’s Hymn is thus:

- 4 stresses/emphases per line

- 3 alliterations per line

- A caesura2 in every line

In terms of the length of the poem and stanzas, there are no hard and fast rules, and in fact, even the above rules are often subverted; for example, some of the lines in this poem use two or four alliterations.

Interestingly, due to the fact that the earliest poetry comes not from written word but from the oral tradition, in the early manuscripts poetry is often written without line breaks. Therefore, modern scholars have used the alliteration to work out the lines.

Using the style of Caedmon’s Hymn, I decided to write a short stanza and test how the form would work in modern English. (The following was written purely to illustrate the form):

Sing to me o’ muse, bring forth my words

And let the meaning, lilting from this

numb mind, measure the metre.

But bereft of syllables, I’ll count in beats

And watch the stress, as I make the break,

Running without reason, against the rest.

Perhaps the easiest part of early English poetry to recreate is the alliteration:

Sing to me o’ muse, bring forth my words

And let the meaning, lilting from this

numb mind, measure the metre.

But bereft of syllables, I’ll count in beats

And watch the stress, as I make the break,

Running without reason, against the rest.

Although it may pose some challenge when writing with a more intentional subject, and I have done it rather crudely, it is not something alien to us, and is used often in modern poetry.

Of course, writing in modern English it is extremely difficult to have only four stresses per line. However, given the clear form of the poem, we can see where the emphases should perhaps be:

Sing to me o’ muse, bring forth my words

And let the meaning, lilting from this

numb mind, measure the metre.

But bereft of syllables, I’ll count in beats

And watch the stress, as I make the break,

Running without reason, against the rest.

I have also inserted commas to illustrate where the caesura would be, although some editors choose to print early English poetry with a physical break between lines to show the importance of the caesura:

Sing to me o’ muse bring forth my words

And let the meaning lilting from this

numb mind measure the metre.

But bereft of syllables I’ll count in beats

And watch the stress as I make the break,

Running without reason against the rest.

This has quite a dramatic effect on the way the poem looks on the page, and modern poetry is definitely concerned with its appearance as well as its meaning and its sound, but it perhaps says more about the editor than it does the poet.

You can see how many challenges are posed by this mix of old and new, but I think it has the potential to produce some interesting pieces, and to change the way I, at the very least, approach and feel about my work. And hopefully, over the next few weeks, I will feel inspired to write something slightly more interesting than the above.

- Except for the “one I am quite fond of”, The Minotaur, which is the product of many careful hours’ work. [↩]

- A break in the middle of a line. [↩]

This was very interesting and useful (for me). I love poetry. I have never studied it or perfected the proper way or way, but I enjoy reading and writing it. Your sample poem was lovely. Thank-you! I learned a couple new things!

Glad to be of assistance!

Literary-speak makes me wet….between the ears, that is. Thanks for this.

You’re very welcome! Thank you for reading.

I always hated poetry at school as I always felt there were ‘rules’ I didn’t know and understand and so I avoided it. I wish I had a teacher who had explained things like this….maybe then I would have been more turned on and less bored… ;)

Mollyxxx

Yeah, it really does take the right teachers to make this stuff so amazing… and they are hard to come by. Particularly before university. Such a shame.

Not sure about poetry being ‘usurped by the rise of the novel’ – I think it’s been subsumed into post 1950s music. Some of the lyrics from the best singer-songwriters are simply beautiful, even when taken on their own – and when set to music, they SOAR.

I would argue – and have argued, actually – that lyrics are very different from poetry. They aren’t less or more worthy, but writing lyrics is a very different discipline. Of course there are poetic lyricists and there are poems that lend themselves well to music, but it’s not the same thing.

In any case, what I meant when I said that poetry has been ‘usurped by the rise of the novel’ is that novels have taken the place of poetry in terms of what people have on their shelves, and what people read for leisure. Before the 18th century, that was poetry. Now it’s novels.